by Jim Rietmulder

Introduction

You have probably noticed two prominent themes at The Circle School: public government and personal freedom. The school is run democratically – part of the public government theme; and students direct their own activity – part of the personal freedom theme.

Focusing on the latter, The Learning Edge offers thoughts about how and why self–direction is important and effective in education, proposing a framework of ideas supporting the practice of self–directed schooling.

Observers agree that The Circle School “works,” but don’t necessarily agree on any particular understanding of how and why. People with differing views on politics, religion, society, culture, and human nature agree that self–direction in schooling is proper and successful, while holding a variety of views about the psychology and philosophy behind it.

In this light, we offer the following essay not as definitive or correct, but simply as one thoughtful perspective to stimulate your own thinking about how and why children learn, and the implications for education.

Jim is a parent, and also a founder and staff member at The Circle School.

Overview

In each person, learning takes place at the boundary between the known and the unknown. We are each born with the ability to detect the limits of our knowledge, and the drive to expand those personal boundaries.

We give our attention – primal, sovereign focus of mind – first to basic physical and emotional needs, and then to higher needs of self-actualization, guided to our learning edges by the compass of curiosity and interest.

Modern research brings science into agreement with common observation regarding learning. Assuming that basic needs are met, personal interest and intrinsic motivation impel us towards greatest expansion and fullest realization of human potential.

Known and unknown

Consider the diagram of an individual person’s “mind space” in Figure 1. The shaded region with an irregular shape represents what the person knows already, and is labeled Known. Everything other than the shaded region represents what the person doesn’t know, and is labeled Unknown. As the person learns, the Known region expands to include new knowledge.

Think of the Known region as a giant amoeba or a monstrous Blob, expanding and changing shape to absorb what is nearby. This image captures a simple truth about learning: learning takes place only at the boundary between the known and the unknown.[1] You can only learn what lies immediately beyond the present boundaries of your knowledge. For example, imagine trying to teach integral calculus to someone who has just learned to count to five; or trying to explain computer programming to a tribal hunter-gatherer who has no exposure to modern technology. Neither will be successful without first covering many other topics, because the target ideas are so far removed from the learner’s present knowledge.

This model applies to all knowledge, not just abstract topics such as calculus and computer programming. For example, you can’t learn to sing until you learn how to coordinate certain muscles in your mouth and throat; and you can’t learn to persuade others of your opinion until you learn to recognize that you have an opinion, and you learn the introspective skills to know what your opinion is, and you learn suitable expressive skills. Education theorist Howard Gardner identified seven kinds of intelligence: language, math/ logic, music, spatial reasoning, movement, interpersonal intelligence, and intrapersonal intelligence.[2] The region of the Known pushes its way into all seven territories. We each have knowledge and learning edges in all sorts of intelligence.

The diagram in Figure 1 oversimplifies. Figure 2 better illustrates the sprawling, explosive character of learning – reaching out in all directions with irregular extensions and borders; narrow corridors leading to large chambers; buds of new learning sprouting everywhere. For a better image yet, imagine the diagram in three dimensions, extending above and below the page. Imagine protrusions and indentations, bumps and holes, hills and valleys, pulled and stretched and twisted this way and that into every shape you can think of. Imagine a long, skinny tentacle ending with a big, fat sphere – an isolated ball of knowledge only tenuously connected to the person’s other learnings. Imagine an air pocket – an apparent gap in knowledge of an otherwise mastered subject or skill. Even in three dimensions, though, the picture falls short of the many – dimensional complexity of human knowledge.

Detecting the learning edge

We are born with an ability to sense the boundaries of our knowledge. Of course we don’t know what lies far beyond, in distant regions of the unknown, but whether or not we are conscious of it, we are able to mentally creep up to the border regions, from inside, and be aware that we are near the edge.

Infants, for example, spend much of their waking time moving their limbs, flailing in what appears to be random motion. They haven’t yet acquired the physical knowledge of how to control their arm and leg muscles. They haven’t yet developed a mental model of three-dimensional space, nor an understanding of objects, nor a recognition of their own bodies as objects.

Yet infants spend hours working at their learning edges, clearly indicating ability to detect and focus attention on them. Like the monster Blob expanding to absorb what is nearby, the infant mind finds its boundaries and expands its knowledge to include the next concept–and the next and the next, each building on what is already there.

It is not only infants who are expert at finding their knowledge boundaries. Research findings, consistent with everyday observations by parents and educators, show that children of all ages are adept at identifying optimal challenges: tasks that are not too hard and not too easy, but are near their own individual learning edges.[3] If the task is too hard, it won’t result in learning because it is disconnected from current knowledge; the expanding Blob can’t reach it. If the task is too easy, no learning occurs because there is nothing new to learn; the learner’s mind already includes that region of knowledge.

You may find support for this idea simply by reflecting on your own experience. For example, it is common to know immediately, with little or no apparent thought, when you are trying to perform a physical task that is beyond your present physical knowledge – the intelligence of movement, in Gardner’s terms. Without effort we can sense when something is too hard or too easy for us, whether it is a new dance step, a problem in mathematics, or your auto mechanic’s explanation of what’s wrong with your car.

The important points are that each person senses the boundaries of their knowledge, and this ability is already fully functioning at birth.

Expanding the boundaries

Not only do infants expertly detect their learning edges, but they also choose to spend most of their waking time pushing those edges outward, expanding the limits of their knowledge. They are drawn to work at their learning edges. Again, this aspect of human nature extends beyond infancy. Children of all ages, given the choice, concentrate their activities at their learning edges. The idea that children’s preferred activity is to expand their knowledge boundaries is not only common knowledge among parents and childcare professionals, but is also well established by cognition research. Specifically, given free choice, children tend to engage in activities that are developmentally just beyond their current knowledge: not too hard, not too easy.[4]

The drive to expand one’s consciousness is inborn. Free exploration and expansion of personal boundaries, with attendant deep satisfaction and joy, may be the quintessence of the human experience.

Again you may find support for this idea in your own experience. Given the right conditions–time, resources, and freedom from other constraints–most of us choose activities that extend the limits of our knowledge in one way or another. Hobbies, sports, reading for pleasure, career advancement, social activity, movies, professional pursuits: all of these expand the boundaries of knowledge. Our choices are motivated by curiosity and interest, which guide us to learning edges and beyond.

Attention

Learning takes place at the boundary between known and unknown, but when and where along that boundary does learning occur? Surely not at every point in every moment? Our minds generally entertain one conscious thought at a time (despite our wishes and attempts to do otherwise); we choose what will occupy us, moment by moment. Attention is the expression of that choice.

Conscious attention is a primal, sovereign, inalienable function of each person. From moment to moment you alone determine on what to focus your attention. Nobody else can do this for you, nor can anyone deny it to you, nor can you escape it. It is your birthright and your natural healthy functioning. Focus of attention may be the most basic choice that you make–and you make it over and over again, perhaps hundreds or thousands of times each day.

Often you focus your attention without conscious effort. For example, internal sensation of hunger gains your attention without your conscious questioning of whether you are hungry. You respond immediately to a loud noise, shifting your attention to its source without apparent effort. Many internal and external stimuli compete for your attention, and you may not ordinarily be conscious of your processes for choosing your attentional focus. Nonetheless, you are choosing, and the choice is yours alone to make.

Attention serves individual survival and growth. We give first attention to stimuli that represent the greatest threats to our survival or well-being, and we shift our attention to adapt to changing threats and opportunities. Hunger, for example, ranks as a high priority, but we won’t pay attention to our hunger while being chased by a lion (which is paying attention to its hunger). Along the lines of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Figure 3), we generally give our attention first to the basic needs of hunger, affection, security, belongingness, self-esteem, and the like.[5]

In the absence of urgent basic needs, we shift our attention to higher needs–meta-needs, as Maslow called them: justice, goodness, beauty, order, unity, and more; the fulfillment of which leads the person towards self-actualization and self-transcendence. Higher needs are as instinctive as basic needs, and their satisfaction is just as necessary to full health. When the higher needs are not met, the person may experience such pathologies as alienation, anguish, apathy, and cynicism.[6]

The higher needs are expressed in our inborn drive to expand our knowledge boundaries, to seek growth and fulfillment beyond the basic physical and emotional needs. Interest indicates the knowledge boundaries that we are most ready and best able to expand. Interest is the compass that points us towards self-actualization.

The exact origins of particular interests within the mind are ordinarily obscure and perhaps unknowable. Beyond the most basic needs, we can’t predict what will interest any particular person at any given moment. Most of us can’t even predict our own interests until they surface at a learning edge.

What we do know is that interest is inborn and crucial to learning, growth, and general well-being. For example, the infant’s interests in learning muscle control, movement, face recognition, and speech are vital to thriving and growth. Interest continues to lead to expansion of knowledge boundaries beyond infancy, beyond basic needs, continuing as the person approaches highest purpose, deepest truth, and grandest joy.

We also know that interest varies greatly from person to person and from moment to moment. Even within families, parents of two or more children often express amazement at how different their children are from one another, particularly in their personal interests, styles, likes, and dislikes. Neither parents nor educators nor psychologists achieve much success at all in trying to predict or direct children’s interests. We simply come to understand that curiosity and interest are personal matters, infinitely rich and variable; important growth mechanisms whose inner workings are mostly hidden from our view.

When the mind is free to pursue its natural inclination, when more urgent attentional demands have been satisfied for the moment, personal interest determines our choice of where to expand our boundaries. Why does a person choose to expand this way instead of that way? Because of personal interest, the inborn guide to self-actualization.

Interest and learning

Interest ignites intrinsic motivation, an internal call to action. Intrinsic motivation is what leads a person to do something for its own sake, for its inherent value to the person, rather than to earn a reward or avoid a punishment. When we are interested in a subject and we concentrate our attention on it because of our interest, we learn quickly and deeply, and we retain what we have learned. Our knowledge boundaries are efficiently and enduringly expanded.

Intrinsic motivation, the fire of interest, burns at the boundaries of the Known. Interest calls us to our learning edges and kindles the fire. Thus inspired, we take action to extend and reshape the boundaries of mind and self.

The connection between interest and learning is clear to most of us through personal experience and introspection. It is therefore not surprising to learn that scholarly studies confirm this common-sense idea. What might be surprising, however, is the strength of the connection that has been discovered by modern research in human cognition. For example, in a study of what accounts for variation in reading retention among third and fourth graders, researchers found that personal interest in the subject was more than thirty times more important than the reading difficulty of the passage![7]

Consider the implications of this finding. We might reasonably speculate that a child can accomplish the same learning in one reading or in many readings of the same material, depending only and simply on the child’s interest in the subject. Or a child might learn the same dance step in one practice session or in many practice sessions, depending only and simply on the child’s interest in being there. Or a child might learn in one exploration what they might otherwise never learn, depending only and simply on what motivates the child’s attention.

Infants and toddlers are commonly afforded the opportunity to work full time on the activities that interest them. It is no coincidence that they learn at such breathtaking rates.

The effect of interest and intrinsic motivation on learning has been so clearly, dramatically, and repeatedly demonstrated that it is virtually indisputable: we learn that which engages our interest. Educators universally recognize this simple fact, and decades of research confirm it. Unfortunately, traditional schools are not designed to engage the power of children’s individual interests. Traditional schools continue to operate on the unrealistic notion that teachers will somehow evoke and synchronize students’ interest, and then pour knowledge into receptive vessels. Common sense and science now agree that life doesn’t work this way.

Punishment and rewards

Seeking to improve on the traditional approach, vast resources have been invested in studies of intrinsic motivation, and we have come to know a great deal about it. Long ago, educators came to understand that punishment severely reduces intrinsic motivation, and therefore holds no promise for enhancement of learning. This finding holds true for punishments of all kinds, and also for threats of punishment.

What about rewards? Intensely studied in the last twenty years, researchers have minutely analyzed all types of rewards and a vast array of methods for handing them out to students. A survey of research on rewards in schools, including 37 separate studies, flatly declares the consensus conclusion that rewards reduce intrinsic motivation.[8] What’s more, it appears that the damage is greatest among children who are highly motivated to begin with.[9] Rewards dull curiosity. It’s that simple. As A. S. Neill observed, offering a reward for something is “tantamount to declaring that the activity is not worth doing for its own sake.” [10]

Rewards and punishment–including grades, adult approval, smiley face stickers, and on and on–lead to less interest in a task, poorer performance, and shallower interaction with the task. Researcher Alfie Kohn surveys the modern scientific literature in detail and concludes that “Rewards and punishments are worthless at best and destructive at worst.” [11]

Controlling tactics versus autonomy

Research about intrinsic motivation is voluminous, showing that all of the following reduce intrinsic motivation and impede learning: grades, testing, other forms of imposed evaluation, telling people they will be evaluated (even if they aren’t), threats of punishment, promises of rewards, pop quizzes, surveillance, hovering, close supervision, calling on children to speak involuntarily, goal setting, unwanted competition. Even personal praise has been found generally to reduce intrinsic motivation and the power it brings to learning.[12]

Worse still, “results clearly show [that] academic intrinsic motivation and anxiety are negatively related.” [13] In other words, grades and other traditional school tactics not only impede learning, but also increase children’s anxiety–an indication that higher needs are not being met. Furthermore, the harder we push, the worse it gets.

Thoughtful self-examination and the preponderance of research findings agree on the simple principle that intrinsic motivation is diminished by controlling tactics. Apparently we naturally resist efforts to bend us to someone else’s purposes. Perhaps our natural resistance to control by others is a wholesome expression of the sovereign nature of attention. Nature is simply keeping us on track, following our internal compass to self–actualization.

The news about intrinsic motivation is not all negative. Research findings are also eminently clear that autonomy increases intrinsic motivation. [14] Giving a person significant control of their activities – self-determination– increases motivation and enhances learning. Self–chosen exercise of our natural gifts of attentional choice and personal interest lead to greatest expansion of knowledge and self.

Perhaps your own experience confirms the principle that self-determination increases motivation. Perhaps, like most people, you find greater enthusiasm for meeting goals that you have set for yourself, and less enthusiasm for meeting the demands of others: think of a New Year’s resolution established for you by your spouse. Perhaps you find greater satisfaction in a day’s activities that you have planned for yourself, and less satisfaction in following plans and activities that someone else has imposed upon you, against your will.

To rebel against encroachment upon one’s birthright of attentional choice is a natural, healthy, wholesome response. To suppress and deaden the inborn compass is to invite loss of direction and loss of enthusiasm for life.

Synergy

Imagine the educating power of interest and self-determination combined! Self-determination supports the natural progress of attention from basic to higher needs. Interest thus aroused ignites the fires of motivation, burning new knowledge and extending personal limits. For learning efficiency, durability, and satisfaction, there is no substitute for personal interest freely pursued.

Indeed, let us do more than imagine the combined power of interest and self-determination. Let us create a place where children can practice both. We’ll call it school.

Seven Kinds of Smart?

In 1983 Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner challenged the common conception of what makes a person intelligent. Our culture and schools, said Gardner, generally focus on two kinds of intelligence: verbal-linguistic and logical-mathematical. But these tell only part of the story of human ability to process information and interact with the world. Gardner proposes that there are at least seven kinds of intelligence that are based in mind-brain structures. We each harbor all seven to varying degrees, and all seven cut across cultural and educational boundaries. The seven intelligences, and some typical skills and activities, are as follows:

- Verbal-linguistic: reading, writing, telling stories.

- Logical-mathematical: patterns, arithmetic, strategy games, experiments, classifications.

- Bodily-kinesthetic: athletics, dancing, making things, sewing, crafts.

- Spatial: mazes, jigsaw puzzles, sculpture, drawing, Legos, images, pictures, star navigation.

- Musical: singing, sounds, drumming, listening, sound-awareness and sensitivity.

- Interpersonal: communicating, empathy, understanding others’ moods and motives.

- Intrapersonal: introspection, poetry, expressive painting, self-understanding.

Symptoms of Interest

Interest is the internal compass that points us towards survival, growth, and self-actualization. When basic needs are satisfied, interest is aroused in higher knowledge and understanding of the world. How can we tell when a person is in the grip of serious interest? After decades of observing, Daniel Greenberg records the following symptoms:

Concentration: Intense, sustained focusing… not readily interrupted by distractions or noise. Often accompanied by irritability when attempts are made to intrude on the person’s attention.

Perseverance: Continued application of energy, without consideration for obstacles or difficulties… an element of stubbornness, bordering on obsessiveness, to carry through against all odds.

Timelessness: Obliviousness to the passage of time and the normal rhythms of life. Regular routines are ignored or postponed. Constraints due to the intrusion of time-related factors are greatly resented – for instance, having to terminate activity due to closing of school.

Tirelessness: Postponement of rest or sleep, often beyond the point of exhaustion. In children, intense continuous activity at a level that would destroy the ability of a normal adult to function – followed by sudden and total collapse.

Self-activation: Self-initiation of vigorous activity… strong driving force to carry through the project by one’s own efforts, to be the designer and implementer of the entire activity. There is no thought of waiting. To the extent that other people must be involved in the quest, their participation is viewed as a necessary evil.

Impatience: Lack of willingness to postpone involvement with the matter at hand. If possible, it is attended to now; if that cannot be, then as soon as possible. Other activities are barely tolerated, and are gotten out of the way with maximum dispatch. The aim is to get back to the activity and to get on with it.

– Excerpted from “On Being Interested” by Daniel Greenberg, Sudbury Valley School Newsletter, March 1993.

The Learning Edge

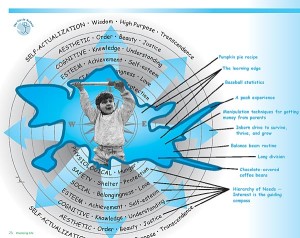

The figure below pictures an expanding mind, superimposed on a map of human development.

Photo by Dee

The squiggly region represents the person’s knowledge. Its border is the learning edge: the boundary between the known and the unknown. All learning takes place at the learning edge, simply because you can only learn that which lies immediately beyond the present boundaries of your knowledge. Ideas and experiences that are far beyond the learning edge are incomprehensible, and everything inside the boundaries, you already know.

The large outward – pointing arrows underneath indicate the human instinct to survive, thrive, and grow. The concentric circles represent levels of growth through the hierarchy of human needs. Basic needs come first – hunger and sleep, for example. Then instinct drives the person’s attention to satisfaction of progressively higher needs, such as understanding, order, justice, beauty, and wisdom.

As the mind expands, higher needs are more often the focus of attention. The compass of personal interest guides the seeker to the learning edge, pointing the way to greatest expansion and fullest realization of potential.

Greatest personal growth – maximum expansion of self – occurs when attention is freely directed by interest to the learning edge.

Footnotes

- Russian psychologist Lev S. Vygotsky (1896-1934) used the phrase “zone of proximal development” to refer to the difference between what a child can do with and without help from others–perhaps the area immediately beyond the “Known”. See Lev Vygotsky, Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (Harvard University Press, 1978).

- Howard Gardner, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (Basic Books, 1983).

- For example, Fred W. Danner and Edward Lonky, “A Cognitive-Developmental Approach to the Effects of Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation,” in Child Development 52 (September 1981).

- “A Cognitive-Developmental Approach…”

- A. H. Maslow, Toward A Psychology Of Being (2nd ed.) (Van Nostrand, 1968)

- Ibid.

- Richard C. Anderson, Larry L. Shirey, Paul T. Wilson, Linda G. Fielding, “Interestingness of Children’s Reading Material,” in Aptitude, Learning, and Instruction, Vol 3, Richard E. Snow, Editor (Erlbaum, 1987).

- Ruth A. Zbrzezny, “Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation: Improving Learning in the Elementary Classroom” Exit Project, Indiana University at South Bend (1989).

- Fred W. Danner and Edward Lonky, “A Cognitive-Developmental Approach to the Effects of Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation”, in Child Development 52 (September 1981).

- Mark Morgan, “Reward-Induced Decrements and Increments in Intrinsic Motivation”, in Review of Educational Research (1984).

- Alfie Kohn, Punished By Rewards (Houghton Mifflin, 1993).

- Lean Lipps Birch, University of Illinois, reported in Punished By Rewards, p72. Also, “A Cognitive-Developmental Approach…”

- Adele Eskeles Gottfried, “Relationships Between Academic Intrinsic Motivation and Anxiety in Children and Young Adolescents”, in Journal of School Psychology v20 n3 (Fall 1982) pp205-215, as abstracted in ERIC database.

- Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan, “Curiosity and Self-directed Learning: The Role of Motivation in Education”, from ED 207 377, ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education, 1981.